Writing Text to the OLED Display

In this expriment, we’ll be figuring out how to start up the OLED Expansion’s screen and writing some text to it using Onion’s Python module for the OLED Expansion. By the end, you’ll be able to boot it up, and write whatever you wish!

The OLED Display

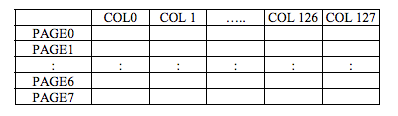

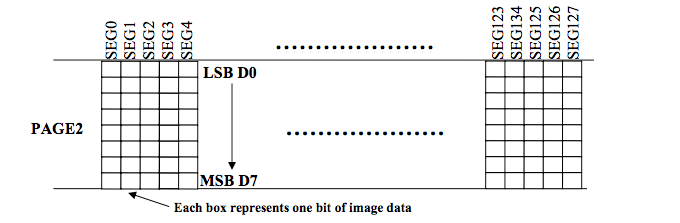

The OLED Expansion has a resolution of 128x64 pixels. It is addressable by 128 vertical columns and 8 horizontal pages.

Each page consists of 8 horizontal pixel rows. When a byte is written to the display, the Least Significant Byte (LSB) corresponds to the top-most pixel of the page in the current column. The Most Significant Byte (MSB) corresponds to the bottom-most pixel of the page in the current column.

The display keeps a cursor pointer in memory that indicates the current page and column being addressed. The cursor will automatically be incremented after each byte is written, the cursor can also be moved by the user through functions discussed later. When writing text to the display, each character is 6 columns wide and 1 page long. This means that 8 lines of text each 21 characters long, can be written to the OLED display.

Building the Circuit

This expriment does not require you to use a breadboard as the OLED Expansion is a complete circuit. Plug it into your Expansion Dock and you’re good to go!

What You’ll Need

- 1x Omega2 plugged into Expansion Dock

- 1x OLED Expansion plugged into Expansion Dock above

Writing the Code

The code we’ll be writing is straightforward: we’ll be calling on the oledExp class from the OmegaExpansion Python Module and using the built in functions to print a bunch of text. For more details on the Oled Expansion Python Class and Module, check out the software module reference in the Omega2 Docs.

Create a file called MAK04-oledWriteText.py and paste the following code in it:

from OmegaExpansion import oledExp

import time

import datetime

import math

# array of quotes that we will be displaying

quoteArray = ['Banging your head against a wall burns 150 calories an hour.',

'In the UK, it is illegal to eat mince pies on Christmas Day!',

'When hippos are upset, their sweat turns red.',

'Cherophobia is the fear of fun.',

'If you lift a kangaroos tail off the ground it cannot hop.']

def main():

# instantiate datetime object that represents a snapshot of the time when this line is run

# we'll be displaying the data (hours, minutes, etc) on the OLED

dateTimeObj = datetime.datetime.now()

hour = dateTimeObj.hour

sec = dateTimeObj.second

# The minute data is stored as an integer in the datetime object, however it needs to have a leading zero for numbers less than 10

# This section first converts the minute to a string, and adds a leading zero if the number is less than 10

minute = str(dateTimeObj.minute)

if dateTimeObj.minute < 10:

minute = "0" + minute

# The 'hour' attribute of dateTimeObj is stored in 24hr format, this part checks for AM/PM differences and converts the time to 12hr format, creating a variable to store the 'AM/PM' string along the way

if(hour/12 == 0):

day = "AM"

hour = str(hour % 12)

else:

day = "PM"

hour = str(hour % 12)

# assembling the time data into a properly formatted time string

dateTimeStr = hour + ":" + minute + " " + day

# create a greeting based on the time of day

if(dateTimeObj.hour < 12):

greeting = "Good Morning"

elif(17 > dateTimeObj.hour >= 12):

greeting = "Good Afternoon"

else:

greeting = "Good Evening"

# Initialize the display

oledExp.driverInit()

# Preps the OLED screen to display text

oledExp.setTextColumns()

# Writes out the time of day to the OLED display in a specific location

oledExp.setCursor(0,13)

oledExp.write(dateTimeStr)

# Writes the greeting to a different location so it doesn't overwrite the time of day

oledExp.setCursor(2,0)

oledExp.write(greeting)

# Writes out one of our quotes 'randomly', again in a new location

oledExp.setCursor(4,0)

oledExp.write(quoteArray[sec%5])

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()What to Expect

After running the Python code, you should see the current current time on the right side of the top row, a greeting on the third row and a random fact on the fifth row.

A Closer Look at the Code

To get the current time, we use the datetime library that is provided standard with Python. We create a datetime object storing the current date and time using the datetime.datetime.now() constructor. We then access the object’s hour and minutes attributes to the retrieve the time values of interest. The we use some logic and mathematical conversion to decide if it is AM or PM and which greeting to display.

For the quote, we use a rudimentary way of generating random numbers to select which one to display.

Date, Time, and Logic

When we check the time in real life, it’s likely because we want to make a decision based on it. Timing is just as important in software and automation. Python’s time library pulls the time from low level operating system commands, and there are built-in functions to parse them into readable strings. We use the time function to make a decision to show ‘Afternoon’, ‘Evening’, or ‘Morning’. You can apply the exact same idea and code to make timing decisions in your own projects to do cooler stuff!

Generating Random Numbers

Random numbers are an integral part of many pieces of software. They are used to generate unique IDs, testing, statistics, and even games (dice rolls, card shuffles are all random!). Here we generate a random number in two steps. First, we get the time in seconds. Next we take the remainder of the current time (in seconds) divided by 5. The resultant number is relatively unordered, and we use that to select which quote we show.

This is a very rudimentary way of generating a random number, and it is not actually truly random! This kind of random number is often called a ‘pseudo-random’ number.

Pseudo-Random vs. True Random

Securing messages on the internet is currently the biggest way random numbers are used right now. Almost all methods of sending and receiving secure messages need truly random numbers. If the numbers used are generated from an algorithm (like the one above), the secure message can be decoded by copying the algorithm and predicting the random number output. Cyber-security is a muchm much larger topic than we can cover here. If you are interested, there’s a great deal of resources available online from very qualified sources. Cloudflare has a great blog post with an excellent example of where pseudo-random numbers fall short in security if you want to read more about it.

Next time, we fiddle with the screen.